Know then that it is the year 10,191. The known universe is ruled by the Padishah Emperor Shaddam IV, my father. In this time, the most precious substance in the universe is the spice melange.

— Princess Irulan’s opening monologue from the 1984 Dune

Whether you've seen the movies or read all the books, if anyone asks you about the timeline of Dune, I'm sure you can confidently say that we're ten millennia after the establishment of the Spacing Guild.

The known universe has been frozen in a state of stagnation: the same Great Houses are battling it out in the open, while various factions scheme in the shadows, and the most constant thing of all is the Spice.

But what if I told you that in the original timeline, the discovery of Spice is relatively recent? I'd argue it's been about a century, give or take.

And all the evidence is in the original book.

Last week, when we were exploring the Faufreluches, I mentioned how it's super weird that the only planet with the universe's most important substance isn't locked down and regulated, but is considered a backwater world where social classes are not observed.

I didn't want to go into it then, but I will say it now: I think that's because it was a backwater world with no value until fairly recently.

But here's some more evidence to support my claim.

The scene that initially sparked my suspicions was the one where Duke Leto and his senior staff get acquainted with the technology used on Arrakis.

Paul leaned forward, staring at the machine.

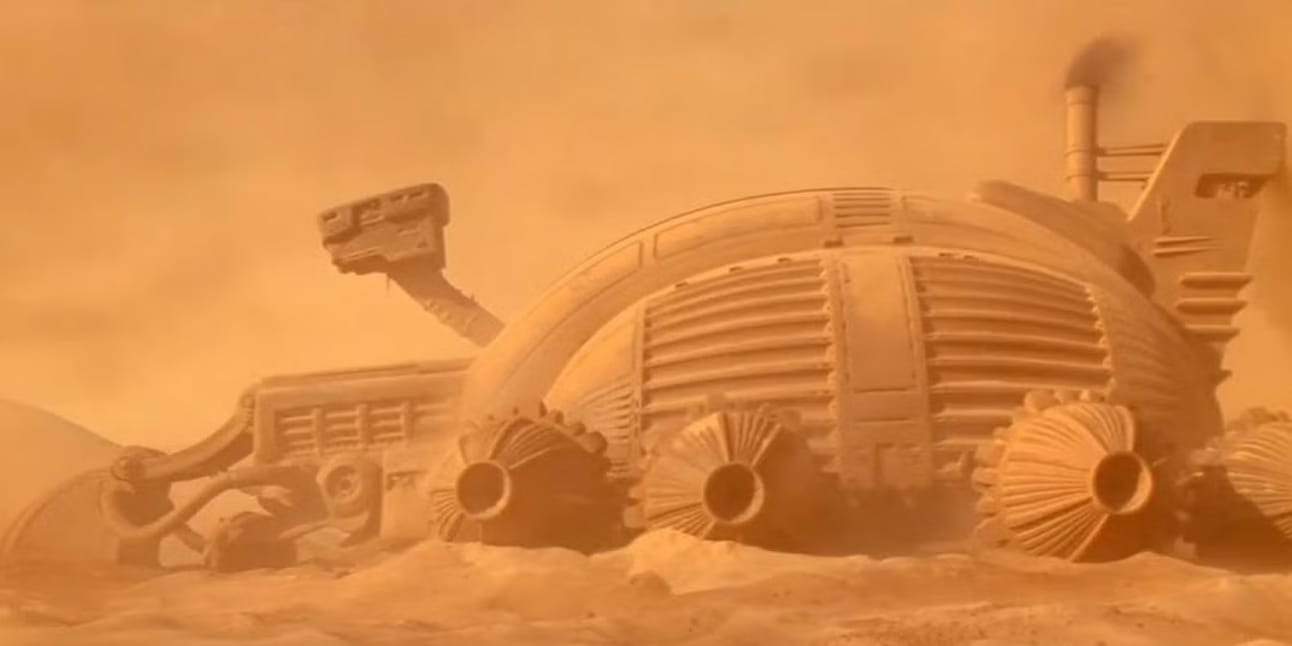

Scaled against the tiny projected human figures around it, the thing was about one hundred and twenty meters long and about forty meters wide. It was basically a long, buglike body moving on independent sets of wide tracks.

"This is a harvester factory," Hawat said. "We chose one in good repair for this projection. There's one dragline outfit that came in with the first team of Imperial ecologists, though, and it's still running … although I don't know how … or why."

"If that's the one they call 'Old Maria,' it belongs in a museum," an aide said. "I think the Harkonnens kept it as a punishment job, a threat hanging over their workers' heads. Be good or you'll be assigned to Old Maria."

— Dune [1965]

The Atreides inherited a harvester that's been here since the very beginning of Spice mining - we know the Navigators rely on Spice, and since the Guild was established 10,191 years ago, that would mean that piece of heavy industrial machinery has been around for at least ten millennia.

Talk about build quality.

So I ask you. Wouldn't this scene make much more sense if the ecologists came in only - let's say - a hundred years ago? Did some testing, figured out Spice, and then the Harkonnen's got their mining rights? We know they've been doing this for "only" 80 years.

Thufir Hawat, his father's Master of Assassins, had explained it: their mortal enemies, the Harkonnens, had been on Arrakis eighty years, holding the planet in quasi-fief under a CHOAM Company contract to mine the geriatric spice, melange.

— Dune [1965]

But 'Old Maria' is just the beginning. Once you know what to look for, you keep bumping into first-draft remnants of a much shorter, more recent history.

Yes, you might call them plot holes that should've been caught in the last edit - but to me, they're much more exciting. If you allow for these "mistakes," you can really enjoy these fragments of what was likely Herbert's original, more compressed timeline that got buried under the epic scope as Dune evolved.

So let's get digging.

When it comes to equipment, that impossibly long-lived harvester belongs to a larger group of ancients: the Imperial Ecological Testing Stations scattered across Arrakis.

Here's Thufir briefing Duke Leto, who gets really excited about potentially salvaging what might be inside them.

"It's said among the Fremen that there were more than two hundred of these advance bases built here on Arrakis during the Desert Botanical Testing Station period. All supposedly have been abandoned, but there are reports they were sealed off before being abandoned."

— Dune [1965]

While we don't get a direct timeline, just a reference to the "Desert Botanical Testing Station period," we get some evidence about when that was in an earlier scene.

Here's Paul getting used to his new room in Arrakeen.

He thought of the filmbook Yueh had shown him—"Arrakis: His Imperial Majesty's Desert Botanical Testing Station." It was an old filmbook from before discovery of the spice.

— Dune [1965]

A 10,000+ year old book? And Yueh just hands it over to some teenager?

Or was it maybe a hundred-year-old, outdated manual no one really cared about anymore? You know, because of the Spice.

We already established that the Harkonnen rule over Arrakis lasted eighty years before the Atreides' arrival. This period is consistently framed as an era of brutal spice exploitation.

The cost of the Harkonnen-Sardaukar attack to retake the planet - equivalent to basically all of the stashed away profits - gives us another clue.

If you think about it, the Baron went all in.

Does that make more sense as an "investment" to (re)take control of a newly vital resource while "dispatching" a political enemy OR just routine political maneuvering in a ten-thousand-year-old feud between two Houses?

When combined with the other evidence mentioned above, the Harkonnen's eighty-year tenure doesn't feel like the latest chapter in an ancient history of spice mining - it feels like the first one.

And speaking of beginnings… the Fremen have been doing something new, too.

While all the offworlders were occupied with the "spice rush", they started terraforming the planet.

To keep it a secret, Stilgar explains to Jessica, they pay off the people with the spaceships.

"We bribe the Guild with a monstrous payment in spice to keep our skies clear of satellites and such that none may spy what we do to the face of Arrakis."

— Dune [1965]

We know this was started by Pardot Kynes a few decades ago.

But if the bribe is to hide the terraforming, and the terraforming only began within living memory, then the bribe itself must be a recent arrangement. The Fremen couldn't have been paying this "monstrous payment" for thousands of years to hide a project that didn't exist yet.

So that would mean that no one in ten millennia had tried to orbit a few satellites above the planet, and just as some people had that great idea, the Fremen were accidentally first to the finish line?

Or is it more plausible that this was a backwater planet with a short history?

An aside: while it's rare to catch Herbert in factual details, he does provide us with two generational yardsticks at the beginning and at the end of the book.

In the opening pages, we learn that Castle Caladan had "served the Atreides family as home for twenty-six generations."

Twenty-six generations is about 800 years, but even using a generous 100-year span to account for spice-extended lifespans, it would only come to 2,600 years. Respectable, but hardly ancient by Imperium standards.

It would, however, seem ancient against the backdrop of a century-old Dune…

And the same is true for the Bene Gesserit breeding program. At the end of the book, we get to know that Paul is the result of a 90-generation-long plan. That's about 2700 years if you count 30 years per generation.

And finally, while this one doesn't help my argument directly, it still shows how Herbert had multiple timelines on his mind as he was doing his world-building.

A couple of weeks ago, I wrote a piece about what the Fremen ate - and was really struggling to reconcile what their original diet might've included vs what Pardot Kynes helped them get.

Because Appendix I credits Pardot Kynes - who arrived a generation and a half before Paul - with introducing vast ecosystems to Arrakis, including kit foxes, desert hares, kangaroo mice, and numerous insects and birds.

Now, they came in with deeper plantings—ephemerals (chenopods, pigweeds, and amaranth to begin), then scotch broom, low lupine, vine eucalyptus (the type adapted for Caladan's northern reaches), dwarf tamarisk, shore pine—then the true desert growths: candelilla, saguaro, and bis-naga, the barrel cactus. Where it would grow, they introduced camel sage, onion grass, gobi feather grass, wild alfalfa, burrow bush, sand verbena, evening primrose, incense bush, smoke tree, creosote bush.

They turned then to the necessary animal life—burrowing creatures to open the soil and aerate it: kit fox, kangaroo mouse, desert hare, sand terrapin … and the predators to keep them in check: desert hawk, dwarf owl, eagle and desert owl; and insects to fill the niches these couldn't reach: scorpion, centipede, trapdoor spider, the biting wasp and the wormfly … and the desert bat to keep watch on these.

Now came the crucial test: date palms, cotton, melons, coffee, medicinals—more than 200 selected food plant types to test and adapt.

— Appendix I, Dune [1965]

Mind you, most of the flora and fauna apparently imported by Kynes were also mentioned in that ten-thousand-year-old book we just talked about.

Names flitted through Paul's mind, each with its picture imprinted by the book's mnemonic pulse: saguaro, burro bush, date palm, sand verbena, evening primrose, barrel cactus, incense bush, smoke tree, creosote bush … kit fox, desert hawk, kangaroo mouse….

— Dune [1965]

But if we accept the ecological impact of Kynes, what exactly did the Fremen eat for the thousands of years they supposedly lived on Arrakis before Kynes arrived? By all accounts, spice coffee and tasty morsels like "bird flesh and grain bound with spice honey" are not anything new.

The 10,000-year Imperium gives us an epic scope and great weight to the story. Paul Atreides doesn't topple a random Empire but an institution spanning both the known universe and time immemorial.

But scratch beneath the surface, and you'll find the ghosts of a more intimate timeline - one where the spice age is a recent revolution, not an ancient foundation. Where Imperial testing stations are yesterday's abandoned projects, not archaeological mysteries. Where the Fremen's secret arrangements with the Guild are desperate recent gambits, not millennial contracts.

Again, I'd like to clarify that I don't consider these plot holes.

Dune is so rich with references, hidden details, and - you know - plots within plots, that I cherish any opportunity to peek behind the curtain and have a glimpse into how it was built.

And I'm happy to see that it wasn't divine inspiration that produced a perfect product, but rather years of work that included multiple iterations of the core idea.

Comparing Spice to Oil and Fremen to Middle Eastern tribes is nothing new; the parallels are obvious.

This just shows you that originally, we would have had yet another similarity to our world: just as the petroleum industry started up about a hundred years before the book was published, so would spice mining have started up a century before the events of the book.

Having said that, if you look at the complete world Herbert built, I think it makes sense that the final result is a hundred times the original timeline.